Hellgate 100k

Hellgate 100k++ Saturday, December 11, 2021 12:01am. Fincastle, Virginia

The Race I Promised My Mother I’d Never Run

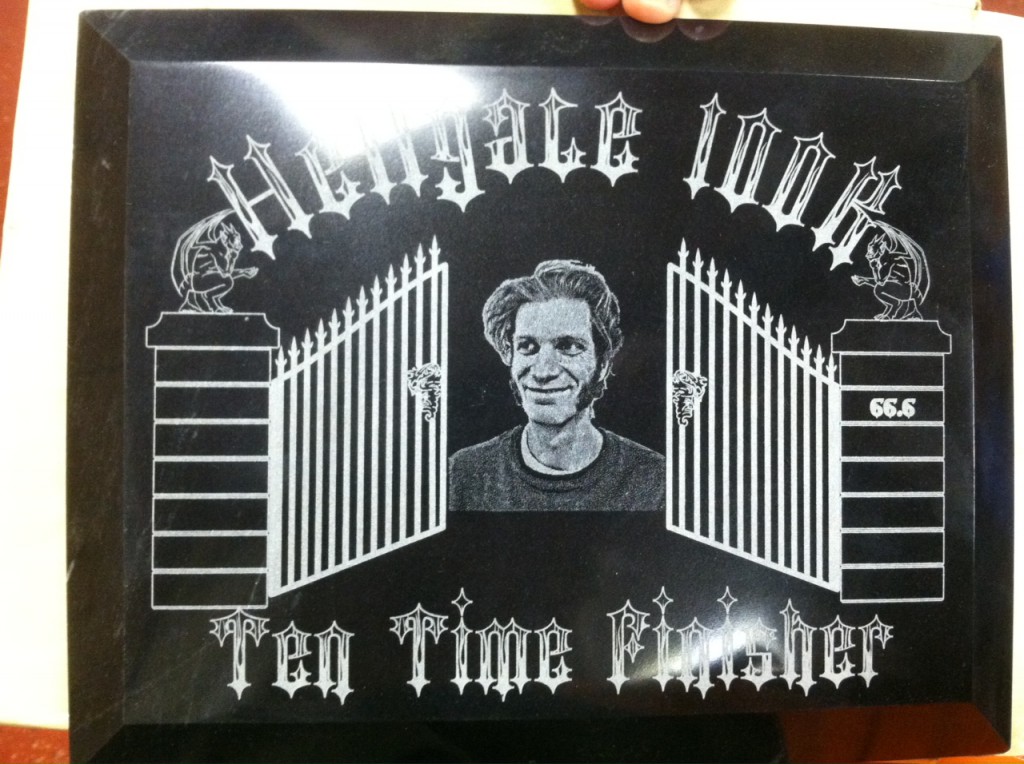

No one was more shocked than my husband when I announced my plan to run Hellgate this year. For more than a decade the Wussies have been needling me about when I would join Aaron at his signature event. Hellgate begins at midnight in December and winds 100+ kilometers through southern Virginia’s Blue Ridge mountains, often at subfreezing temperatures and over loose ankle-breaking rocks hidden under piles of leaves. Aaron is one of the “Fearsome Five” who have run the race every year since its inception in 2003 (the streak is now at 19). It’s not just a race for him, but an end-of-year purification ritual.

But just the mention of Hellgate made me shiver. Every winter I dreaded watching Aaron limp off to his green Jeep Wrangler and drive off to the madcap race that destroyed him. When I started dating Aaron in 2011 he was unknowingly infected with Lyme disease. His suffering came and went in waves much like the COVID-19 pandemic. He developed strange symptoms like heart palpitations, skin peeling, rashes, and bursitis in his heels. We had no idea what was wrong with him. By 2013 he struggled to get out of bed in the morning. In the weeks leading up to Hellgate I would shake my head and warn him, as his medical expert girlfriend, of the risk of permanent damage to his system. But I knew not to stand in his way. To take my mind off his suffering I would join friends on bourbon-fueled trots along the Bull Run trails at the VHTRC Magnus Gluteus Maximus 50k fatass. The party ran all afternoon at Hemlock and every time my mind drifted back to Aaron struggling to stay upright somewhere in southern Virginia I just drowned another swig of bourbon.

Aaron eventually got his Lyme disease diagnosed and treated, with a little help from an infectious disease expert girlfriend who bulldozed through an incompetent medical system. (If another doctor tried to pull on me that Aaron was just getting old and can’t run long distances anymore I would have punched them in the face.) After six weeks of doxycycline Aaron recovered from the acute symptoms of Lyme, but continued to experience bouts of exhaustion, chronic heel pain, and skin peeling. It did not help that he was overworked and overstressed, juggling a day job as a software engineer while launching a new technology start up. I was nervous about starting a family, fearing the sleep deprivation and stress of raising a baby would trigger a relapse.

But in 2018 our son Bjorn arrived, with bright blue eyes and platinum blonde hair. After years of me watching Aaron suffer, the tables turned and Aaron had to watch me come undone. I’m not sure what is worse, to be the sufferer or the helpless onlooker.

Over the Baby Bump

I knew starting a family would be a challenge. I was trying to do something few women pull off. There are few female scientists in my field to begin with (I study computational biology, a cross between molecular biology and computer science), even fewer who are group leaders, and exceedingly few who have young children. The mothers who do survive in my field do so because they have extra supportive bosses. I had the opposite.

I lost my job as a research scientist at the National Institutes of Health in October 2020. I had worked there 12 years without incident, led a highly productive team, and was particularly valued when the pandemic hit because I use genetic data to track SARS-CoV-2 evolution. So my dismissal caused a stir, internationally. The community of infectious disease epidemiologists is small and tight-knit and the big name professors in my field offered to write letters to NIH leadership to protest my termination. Against signs of resistance, my boss had to cover his tracks fast. So he made up stories, falsely claiming I was terminated because I was in trouble with HR for harassing colleagues. I waved my spotless HR record around like a white flag to clear my name, but leadership looked the other way. People rise through government ranks by stepping on women, not sticking out their necks for them.

Suddenly I understood why so many American women quit science, especially after starting families, and my sudden unexpected job loss launched me towards the door. I told Aaron I wanted to move to Scandinavia, where my ancestors still live and mothers are supported with maternity leave, free child care, and tend to stay in the workforce. But being a distance runner for the last twenty-five years helped me understand the natural cycles of downturns, as I chronicled in an essay called “Over the Baby Bump” published earlier this year in Science magazine. Here’s an excerpt*:

“I realized I was in danger of repeating a past mistake of quitting prematurely instead of giving myself time to adapt. Twenty years ago, I was a promising high school distance runner, with a boyish frame that helped me capture title after title. But during puberty I temporarily got fleshier and slower. Dieting and intense workouts only accelerated burnout until I gave up and quit, feeling broken. Years later, I dusted myself off and began trail running in the mountains. When I finally joined the college track team, I raced faster than ever and proved I did not need to be a flat-bodied pixie, I just needed time and space for my changing body to adjust. I have not stopped racing since.

I’ve learned, twice now, to keep lacing up. The pandemic was my tipping point as a working mom, but I survived by reaching out to savvier women who gave me perspective. I’ve now secured a better position at another branch of NIH that maintains my research independence while offering greater job security. This fall I’ll be heading to my new office just as my toddler begins his first day of preschool. Other kids will surely push him down and snatch his toys. But I’ll let him know the same thing happens to his mom, and we dust off, redirect, and embark on new adventures together.”

* I had to do a fair bit of sugar-coating to fit my essay on the one print page Science allotted me. More details about my struggles as a high school runner are available in previous blogs, as is the trauma I experienced during the pandemic.

There’s a Book For That

Getting canned taught me several lessons. First, I discovered how strength I derive from distance running carries over to everything I do in life – my career, my family, my friendships. Getting pushed off a cliff by my boss temporarily made me feel weak and helpless, but this just drove me to get stronger. Being a female scientist does not get easier as you advance. You either quit or get tougher. Ultrarunning offers a path forward. And I knew just the race.

The second lesson is that women trying to do difficult things need support, sometimes quite a bit of support, and asking for help is not a sign of weakness. After I lost my job a group of amazing women scientists rallied around me and Zoomed every week until I was back on my feet with a new job. People are generally happy to help, especially when you’re a person of action and they get to be part of the rebound (that’s not what I meant, you dirty reader!).

I also learned that you can pay for help. There are specialized therapists with PhDs who can mend your brain the same way an orthopedist mends a broken leg. I discovered in pregnancy there are experts for virtually everything, even pelvic floors, and hunting for the right expert can end a lot of suffering. New moms needn’t resign themselves to living with anxiety and depression, or wearing pads the rest of their lives.

I also learned there is a body of scientific literature on nearly every topic. One day when I was trying to figure out why my boss soured on me I googled “People who ruin your life” and discovered books and scientific studies on the ~10% of Americans with known personality disorders (borderline, narcissist, psychopath, etc.). Suddenly everything added up. My boss’s behavior fit a well documented pattern. Before you freak out about the possibility that 1 in 10 of your friends and family are psychopaths, recognize that most people with these disorders (including my boss) are highly personable 99% of the time and easy to work with. They selectively target people (often their spouses). But they cannot be effective liars/manipulators unless they are charming and win people to their side first. Last thing, if you begin to worry that you might one of these personality disorders because sometimes you charm or play victim cards, don’t worry, the defining feature of these conditions is an inability to be self-aware or self-question.

The third lesson I learned was that I picked a good husband. When I fell off the cliff Aaron had to mop up the bleeding. Between the pandemic, the toddler, and the boss from hell, our marriage was seriously stress-tested. It passed because I learned how to follow Aaron blindly each time I slipped into darkness. I learned to trust him. So when he said I could finish Hellgate, even without much training, I just nodded.

Still, practically speaking, I was scared shitless of Hellgate and needed one more thing: a friend I could depend on, even when things got messy, the type who holds your hair back while you puke.

Normal social support evaporated during the pandemic. But you never know who in your vast social network is going to rise to the occasion when you need them most.

The Lapointes

Aaron did 17 Hellgates without crew. But in 2020 he couldn’t get a ride to the start of Hellgate in a car of strangers and or crash for the night on the couch at Camp Bethel without breaking our six-person family COVID bubble that included our son’s three high-risk elderly grandparents. He needed a trusty chauffer. So Aaron called on his childhood friend Matt Lapointe. Matt is dependable, understands science, and was upvoted unanimously by all six members of our family bubble.

This time I didn’t feel pity when Aaron packed his bags for Hellgate, but envy. I, the one with high social needs who was really suffering in our restricted pandemic bubble, was left behind as Aaron indulged in a weekend road trip with the boisterous Lapointe boys. Running 100 kilometers seemed a stiff price of admission for a weekend getaway with friends, especially at a time when I was barely running, depressed, and unable to get my heart rate above 150. Still, I wanted in.

When Matt returned I got to see Hellgate through the fresh eyes of a non-ultrarunner. Matt didn’t paint Hellgate as a sadistic event designed to maximize monstrous weather, sleep deprivation, mind-numbing terrain, and stupid water crossing at mile four to get frozen feet. Matt just saw Hellgate as awesome, a wild romp of an adventure against varied and unpredictable elements. He and his teenage sons were enthralled by the later sections of the course they ran with Aaron. They couldn’t wait to crew again in 2021.

Hellgate left such an impression on Matt that he resolved to pursue his own lifelong dream of running a marathon, which was put on hold during two decades of raising a three-boy family. Aaron and I became Matt’s unofficial coaches, tailoring his marathon training plan. Matt probably didn’t realize it, but he was the one helping us. During the spring of 2021 Matt was the first person Aaron and I ran with during the pandemic. My depression started to lift as we laughed and snorted on the Glover Archibald trails. By August 2021 we all did the Luray International Triathlon together. My heart rate was finally back up again.

Bring in the Professionals

I ran my first ultra in 2009 on a dare. I had just moved to DC and discovered a group of ultrarunners living next door. I joined their death-defying Tuesday night trail runs simply because I was lonely in a new city. And I liked the post-run part where we drank at Cleveland Park Bar and Grill until we started making poor life decisions. One June night I was talked into running the Laurel Highlands 50k that upcoming weekend with Keith, Amy, and Mitchell. I set a course record. After that, I reflexively shot down anyone who tried to coax me into running another ultra. Whatever the opposite of “hooked” is, I was that.

The Wussies were mystified by my lack of interest in Hardrock, Western States, MMT, or other mythic quests they dangled before me. I had the natural endurance to run Catawba and other ultramarathon fatasses when tricked into believing we were going shorter. There was an obvious gulf between what I could do physically and what I thought I could do.

The gulf formed when I was fifteen out of self-preservation. My rookie cross country season I won the state title and suddenly the screws were put in. I had a complicated home life, which I’ve written about previously. I shut running down out at the end of high school because I was mentally and physically destroyed. I returned to run on my own terms in college, earning All-America, and took up marathons in grad school. But I refused to train, wear a watch, or focus on a goal race. Aaron discovered I was willing to bumble around in the woods for hours, chatting and stopping for mushrooms and woodpeckers. I raced fiercely when the mood struck me. But as soon as Aaron referred to something as a “training run” I stiffened. That was not me anymore. Over the last twenty years any success I had at races was despite myself.

But the pandemic gave me no choice: begin therapy, fight demons, or lose everything. It is not a coincidence that I signed up for Hellgate the month after I graduated from a 9-month course of cognitive behavioral therapy. Yes, I’m sure people find it hilarious that I regard running 66.6 miles as a sign of improved mental health.

A Fluke of Timing

Had the Hellgate application arrived any month other than October 2021 I would not have applied. I ran a grand total of zero races in 2020, when I was depressed and barely running. My depression began to lift in May 2021 after I got vaccinated and began to spend limited time with friends again. By September my son was finally enrolled in preschool, I ran Big Schloss 50k, got a new job lined up, and I completed all my major therapy goals. In early October I sent in my Hellgate application. I doubted I would be accepted, but everyone was convinced Aaron had an “in” with race director Dave Horton.

But Matt and I share a weakness for soccer. One night a new guy showed up at WUS named Vivian who played on a DC coed soccer team. I knew I was in trouble. I love soccer and only don’t play anymore because I always get injured. But I’ve had so few indulgences during COVID, I thought I could get away with just one game on Halloween morning. While I was playing I was high as a kite and it was totally worth it. I was beaming for days. But in the process I predictably gummed up the same Achilles I injured playing varsity soccer in college. The tendon wasn’t wrecked, but I did have to scratch every training run left on the calendar: Potomac Heritage 50k, Richmond Marathon, Vicki’s Death March, even the Alexandria Turkey Chase. The week before Hellgate I feared I would have to scratch my goal race too.

Show Time

On race day I had serious doubts about my fitness. I had only trained a couple weeks from late September to mid-October. The pandemic, motherhood, and losing my job had robbed my sleep and ground me down over the past two years. Given my condition, was this really the year to attempt the race that chewed up my much stronger husband?

But my Achilles was quiet, the weather was unseasonably warm, and I had much to be thankful for. Standing on the starting line in shorts, I whispered to Aaron that even if the race was a bust I was proud of myself just for lining up and starting. Knowing how much resistance I had overcome just to get there, he heartily agreed.

Aaron tried to give me some last-minute tips about the course. No one knows more about the ins and outs of the Hellgate course than Aaron. Apparently Aaron has written a detailed race report chock full of helpful details that people rave about. I have never read it. I like to run blind. (Aaron did finally succeed in convincing me to wear a watch for data collection but I refuse to look at it.) The only thing I remembered from Aaron’s repeated attempt to dish me Hellgate intel over the last few months was that (a) there were pierogis somewhere, (b) there was a big climb and then a big downhill to the finish, (c) not to stop at aid station 4 because it’s cold, (d) not to use the rocks to cross the stream because I’ll slip and fall in, (e) not to go too fast downhill because rocks move, and (f) there are a lot of leaves.

The “Cling to Trevor’s Skirt” Section

I am admittedly scared of running alone in the woods in the dark. This problem arose repeatedly during the pandemic when our WUS runs lost attendance and I occasionally found myself alone with my headlamp in DC’s Rock Creek Park, my stomach tied in knots. Aaron couldn’t join me because our good friend who used to babysit Bjorn while we ran WUS died of brain cancer this past year, yet another gut-wrenching tragedy during the pandemic. Running solo in the city’s shadowy woods brought out my worst feelings of being alone, abandoned, vulnerable, and afraid.

Soon I found myself running alone at Hellgate in the dark in a pea soup fog on a trail that no longer resembled a trail. I panicked, convinced I was lost and soon to be axe-murdered in the wilds of southern Virginia. When I finally caught up to my friend Trevor I resolved to stick with him at all costs until daylight. There were costs.

I can’t say for certain why I barfed four times at the mile 22 aid station. Maybe the puking came from hours of running in fear. Maybe it was the mysterious disappearance of my Cheez-its, which I know I stashed in my pack. Maybe Trevor’s pacing was not right for me and lesson 1 of Hellgate is to run my own race. Or maybe it was just the annoyance of running with Trevor. I like Trevor and his sense of humor. But when you’re struggling it can be hard not to begrudge a guy for whom everything seems to come so easy. Trevor continued his amazing race lottery streak this year by getting into both Western States and Hardrock. While I spent the week before Hellgate stressing to get a SARS-CoV-2 study published at Nature by day and barely sleeping while my son coughed with croup all night, Trevor and his wife sunbathed in St Lucia while both babies stayed with grandparents. I don’t know who Trevor paid off to get his life, but I want in.

In truth, my puking at mile 22 fit a well-documented pattern. I have a history of puking during ultramarathons when left to my own devices, but tend to be a happy camper when Aaron is crewing or running with me. It therefore comes as no surprise that the arrival of the Lapointe crew turned my Hellgate around.

Lapointes to the Rescue

The Lapointe family learned pretty quickly that crewing for me is not like crewing for Aaron. The first time they saw me during the race I was turned away vomiting heavily beside the aid station #4 tent.

I waved Trevor on when it was clear I would be chair-bound for a long while. I don’t know how long I sat in that chair. But it was long enough to get 2 Ensures down, a cup of soda, and some Pepto bismol tablets, courtesy of Marty Fox. Sadly, this all would prove to be a waste of time when I threw up it all up ten minutes later down the trail.

This was an unhappy section. I was alone again in the dark fog. It was cold and windy. I kept vomiting. The long night was coming to a close and I was ever so tired. I could see no other headlamp lights in front or behind me and I kept panicking that I had strayed off course and was lost. My IT band killed. I still had so many miles to go.

But I was always happy to see the Lapointes. Matt and the boys were eager to help at the famous breakfast aid station #5. Matt began listing off the fares: eggs, hash browns, sausage, bacon…. He couldn’t finish the list. Just the image made me queasy and I vomited in my own mouth. The terrified boys leapt backwards. But fortunately I didn’t have much in my stomach to come up. The faces on the boys made me laugh. Sometimes a hard laugh is all it takes to change the mood. “Fuck it, give me the bacon,” I told Matt, as I dragged myself off the bucket. I headed down the road with a little ginger ale in my stomach and two greasy bacon strips in my paw. “I promise to eat these!” I lied.

Every now and then Aaron suggests I take a page from Seinfeld’s George Costanza and do the opposite of what I think I should do. I decided that this was that time. Forget gels, forget gummies. Might as well try bacon. My stomach couldn’t get any worse. What did I have to lose?

I nibbled on the end. I couldn’t eat the bacon, but I liked the taste of salt and fat so I sucked on it. For the first time since puking my stomach seemed to like something. I ate a Cheez-it. I kept it all down. Small victories.

The sun was rising, birds were chirping, and the Blue Ridge mountains were cinematically enveloped in wisps of thick white clouds. How could clouds that blinded and terrorized me at night now look so peaceful from a distance in the daylight? I’ve looked at clouds from both sides now, I thought (Joni Mitchell).

I allowed my tired brain to stop fretting about whether I wasn’t eating enough (I wasn’t), what the sharp pain in my heel was (a thumb-sized blister), or whether my IT band hurt from sitting in the chair too long and getting frozen (probably). I was just content to still be out there in the woods, moving forward in the early light. The terrain changed as I approached the race’s midway point and the meandering single track became pleasantly more runnable.

At one point a man behind me charged into a stream, seeking cold water to sooth his aching legs. I laughed out loud, recalling how my friend Daniel had the same idea during British Columbia’s Fat Dog 70-mile race (spoiler alert: it only made his legs hurt worse).

Marmots Heart Pacers

At aid station 7 Andrew Lapointe officially became my first pacer ever in an ultramarathon. I loved it. Where have pacers been all my life?

The final 20 miles were the best part of the race. I learned that blisters and IT bands don’t always get worse. I discovered I can somehow run 66 miles on only a handful of Cheez-its and some soda. I learned that no matter how much pain I was in, I was content as long as I had Lapointes for company. Andrew was silent company, which was fine by me. He only had one job, which he excelled at: saying nice uplifting things to runners we passed. I had no idea what to say to people who were clearly hurting so much, and was ever so grateful to have Andrew to cover for me.

I was actually pretty nervous about Matt pacing me because I didn’t think he knew what he was getting into with all the rocks and leaves. Matt ruptured his ankle playing soccer last spring and needs surgery. I gasped every time I heard him trip behind me. Matt kept instructing me just to worry about myself. I tried. Overall, Matt was a wonderful pacer whose Monty Python lines kept my spirits high (He got better).

Aaron finished an hour or so ahead of me, but we sort of ran the last section together in spirit. Our watches later showed that we ran the final 14 miles from aid station 7 in almost exactly the same time (I was just 2 minutes faster). Breaking it down section by section we seemed to be on exactly the same pace. (Actually, all my race data from the final sections all comes from Matt’s watch. since I never noticed that my watch stopped at mile 24.)

I was losing the race by hours, I wasn’t even top 5 women, yet I swelled with pride. I had conquered something. Not a mountain or a clock or another runner. Just myself.

Aaron was stunned when I trotted across the finish line in just under 15 hours. News was spotty along the course and the last he’d heard I was puking and struggling and likely on pace to finish just under the 18-hour cutoff. I gave him and Horton big hugs.

Because of COVID-19 we didn’t get to stick around and socialize at Camp Bethel, missing a key part of the Hellgate experience. Plenty of people were hanging out on couches and I really wanted to stick around to chat. But I knew too much about omicron.

But I’ll be back next year and probably some more years after that. No, I’m not going to start a streak or go for a set number of finishes. That’s Aaron’s thing. And maybe I won’t like Hellgate in a freezing year when my fingers don’t work. But I get why people come back to this race year after year. Every time I ran through a gate at the end of a forest road I pondered the meaning of “gate” in Hellgate (the “hell” part is obvious). Most races are just races. But some races are portals, and the version of you at the end is not the same as the version that began. I never thought I’d say this, but I’m ready to put myself through the portal again.

Final Note

I’m aware most of this blog describes my journey just to get to the start line. This accurately reflects the breakdown of my struggle: 90% just getting to the start, 8% just getting through the first half, 1.5% getting through the second half, and 0.5% surviving the road trip home (yup, I gave the Lapointe family one last scare by puking into a Sheetz bag in the back of their van, my body’s final rebellion).

Afterward

Hellgate is not for everyone. Aaron insists Hellgate is way harder than an Ironman. Most of my friends would not run 66 miles if a gun were put to their head. But Hellgate is worth experiencing once in your lifetime, even as a volunteer, crew, pacer, or spectator. There’s a strange magic to this race. Matt insists he got more out of Hellgate than Aaron or I did. Next year he promises to run all three sections where pacers are allowed. My blog is light on useful course description but if you are actually interested in running Hellgate yourself and need real intel just read Aaron’s old race report: https://blog.vestigial.org/hellgate-overview/

Archives

- ► 2024 (2)

- ► 2023 (3)

- ► 2022 (3)

- ► 2021 (9)

- ► 2019 (13)

- ► 2018 (7)

- ► 2017 (16)

- ► 2016 (27)

- ► 2015 (27)

- ► 2014 (29)

- ► 2013 (26)

- ► 2012 (42)

- ► December (9)

- 2013: another year, another chance to try to not f&*k everything up

- A White Canaan Christmas

- A very merry fat ass

- The Long-Awaited Weinberger WUS

- Survey Response

- Team Floo Fighters Jingle All the Way

- Neil Young versus the Silver Diner juke box

- Um, ignore last posting - guy is CREEPY

- Looking for Lost Love on Shady Grove Road

- ► November (3)

- ► October (6)

- ► September (7)

- ► August (1)

- ► July (3)

- ► June (5)

- ► April (4)

- ► March (2)

- ► February (2)

- ► December (9)

- ► 2011 (69)

- ► December (2)

- ► November (5)

- ► October (4)

- ► September (5)

- ► August (7)

- ► July (4)

- ► June (7)

- ► May (15)

- Luna's Beer Mile

- Happy birthday, Mario!

- Kerry's Death March - May 21, 2011

- A moment in time. The first WUS run.

- Kerry's Death March

- Choose Your Own Adventure

- The Bear

- Come hither. Drinketh from the WUS cup.

- Neal's take

- When did it happen?

- When will it happen?

- NIH Take a Hike Day

- If it ain't on video, it didn't happen

- The REALLY big question

- Beer Mile: Post-Race Coverage

- ► April (16)

- Layers

- Thoughts of a beer-miler

- Beer Mile Haiku

- Beer Mile: Post-Race Coverage Preview In Which Sean B Expresses The Consensus Emotion On The Topic Of Beer Miles

- Beer Mile

- Beer Mile: Pre-Race Coverage

- Beer Mile Logistics

- Sean Thumb

- Donut Run

- Frisco Ultra Contingent

- Logistical Information for Inaugural WUS Donut/Beer Run Series

- WUS shirt

- Charlottesville Marathon

- Bull Run: A 50 Mile Sonnet

- Trail Maintenance in Rock Creek Park

- ► March (4)

Recent Comments

- Kirstin on WUS Awards 2023

- Jeanne Abbott on Ride ‘n’ Tie: The Wildest Trail Race You’ve Never Heard Of

- Courtney Krueger on Ride ‘n’ Tie: The Wildest Trail Race You’ve Never Heard Of

- Scott Fuller on The Mission

- Matt Woods on How Running Saved My Career as a Scientist