How much do you know about Greg Lemond?  Maybe you’re aware that he won a couple Tour de Frances back in the 1980s.  Perhaps you even heard the incredible story about how, right after winning his first Tour, his brother-in-law accidentally shot 30 pellets into his vital organs while hunting turkeys in California (no relation to Cheney), preventing any attempt to defend his title the next year.

Or maybe, like me, you must shamefully admit that Lemond’s name may ring a bell, but honestly hadn’t even heard of the Tour de France until Lance Armstrong came along.  In my partial defense, I was 5 years old when Greg Lemond became the first American to win the Tour de France in 1986.  And still only 9 when he won his third and final Tour in 1990.  And Lemond kind of fell out of public favor during the long Armstrong Era, when Lemond’s quips about rampant drug use were not taken kindly by Armstrong’s massive fan base, including the media (Lemond’s quick fall from Golden Boy into obscurity is just another example of the long reach of Armstrong’s circle of destruction).

But if you don’t know much about Lemond, you need to stop what you’re doing and pick up a copy of Slaying the Badger: Greg Lemond, Bernard Hinault and the Greatest Tour de France.  After reading Richard Moore’s book and watching the EPSN 30-for-30 documentary based on it, I’ve decided that Greg Lemond is my favorite athlete of all time.

Whoa, there, don’t get your panties in a twist.  I’m not saying Lemond is the greatest athlete of all time.  I grew up watching Michael Jordan, whose body movements made Carl Sagan rethink Newtonian physics.  But while Jordan inspired awe, Lemond melts hearts.  I watch a ton of ESPN 30-for-30 documentaries, including the obscurest of great sports stories (one of my favorites is The Best That Never Was about Marcus Dupree, high school football legend).  And as far as I’m concerned, Greg Lemond’s is the greatest.

If you haven’t become addicted to 30-for-30s, toss that one on your list as well.  These short films were originally 30-minute clips on 30 interesting sports figures to celebrate ESPN’s 30th anniversary.  They were such a hit that now they’re produced every year and in longer 1 hr+ versions.  30-for-30s are the antidote for anyone who feels ill every time the Olympics roll around and we’re subjected to those sappy canned stories of triumph over adversity (or expected to be excited to learn that Michael Phelps eats a lot of pizza).  If you want happy endings, stick with NBC.  The athletes that makes it in that perfect Disney way (hard work and believing) are kind of boring.  Bring on the athletes that reflect our own messy, imperfect lives, filled with psychopaths (see The Price of Gold about Nancy Kerrigan, and Tonya Harding) or gruesome violence (see The Two Escobars and the interweaving of drug cartel violence and soccer in Colombia, leading to the most tragic event in World Cup history).

If you haven’t become addicted to 30-for-30s, toss that one on your list as well.  These short films were originally 30-minute clips on 30 interesting sports figures to celebrate ESPN’s 30th anniversary.  They were such a hit that now they’re produced every year and in longer 1 hr+ versions.  30-for-30s are the antidote for anyone who feels ill every time the Olympics roll around and we’re subjected to those sappy canned stories of triumph over adversity (or expected to be excited to learn that Michael Phelps eats a lot of pizza).  If you want happy endings, stick with NBC.  The athletes that makes it in that perfect Disney way (hard work and believing) are kind of boring.  Bring on the athletes that reflect our own messy, imperfect lives, filled with psychopaths (see The Price of Gold about Nancy Kerrigan, and Tonya Harding) or gruesome violence (see The Two Escobars and the interweaving of drug cartel violence and soccer in Colombia, leading to the most tragic event in World Cup history).

I think you’ll also appreciate Slaying the Badger more if you’ve seen the film The Armstrong Lie.  Lance Armstrong left a deep stain on sports.  I will never be able to witness a heroic athletic feat again without a gnawing doubt that it might not be clean.  But that’s not why I hate Lance Armstrong.  He’s in good company: Mark McGuire, Marion Jones, they all share responsibility for the mutilation of sports.  But what sets Lance apart is the way he systematically took down innocent people who, justifiably in turns out, were not convinced he was clean.  He tore their lives apart.  He made them outcasts.  He abused his fame and power to bully and ruin them financially.  If he were just a cheater, I could forgive.  He was a monster.

I think you’ll also appreciate Slaying the Badger more if you’ve seen the film The Armstrong Lie.  Lance Armstrong left a deep stain on sports.  I will never be able to witness a heroic athletic feat again without a gnawing doubt that it might not be clean.  But that’s not why I hate Lance Armstrong.  He’s in good company: Mark McGuire, Marion Jones, they all share responsibility for the mutilation of sports.  But what sets Lance apart is the way he systematically took down innocent people who, justifiably in turns out, were not convinced he was clean.  He tore their lives apart.  He made them outcasts.  He abused his fame and power to bully and ruin them financially.  If he were just a cheater, I could forgive.  He was a monster.

I know there’s been a lot of debate about whether Lance should be welcomed into the trail running community.  I don’t believe the science is there to justify excluding him (we still don’t understand the long-lasting effects of doping).  And it would be a slippery slope to start excluding folks just because they’re terrible people.  But it’s completely mystifying to me how anyone could look him in the eye and pretend he’s in the same category as, say, Marion Jones, like he’s just a guy who made a terrible mistake.

Except for both being talented American cyclists, Greg Lemond is the exact opposite of Lance.  You think George Washington’s impressive for being honest about a little cherry tree?  Try removing an organ for the sake of integrity.  When Lemond was trying to return to cycling after accidentally being shot in the chest by his in law, he ramped up too quickly and needed to have a second surgery.  To avoid having to inform his cycling team in Europe, he somehow convinced his doctors to remove his appendix as well, so he could just say he’d had an appendectomy.  That way, technically it wasn’t a lie.

Lance Armstrong is famous for winning Tours, using drugs, and a bunch of other things (lying, helping people with cancer, screwing over Sheryl Crow).  But one of his impressive feats is the way he controlled the peloton.  Lance was the consummate bully.

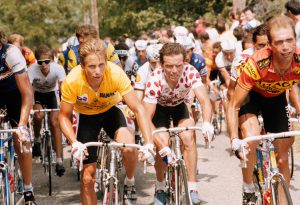

Lemond’s great rival Bernard Hinault also admits that his five Tour victories were not just feats of skill and stamina.  Hinault used his domineering personality to psychologically bludgeon the other riders into submission.  Hinault, the grizzled French mega-hero, got the name ‘Badger’ for his clenched determined jaw and improbable feats of fortitude, such as climbing back on his bike to finish a stage bloodied after riding off a cliff.  Winning the Tour is a heck of a lot easier if you can get the other riders to refrain from attacking when you don’t want to attack, and to not take unnecessary risks that could put you in jeopardy.  Hinault had enormous power of intimidation and an imposing temperament that famously punched a protester at the Tour.  Whereas Hinault perfectly fit the European machismo image of Tour Patron, Lemond’s sunny easy-going Californian disposition could never domineer his own team, let alone the entire peloton.  Their differences made for a very interesting (or, from Lemond’s perspective, torturous) 1986 Tour.

Most sports are fairly straightforward.  Sure, no one really knows what off-sides is in hockey.  Even after winning my 7th grade wrestling championship I still don’t know what I got points for.  But at least in most sports you know (a) who your opponent is, and (b) whether you’re competing in a team sport (in which you win or lose as a team) or an individual sport (where you win or lose as an individual).  If this seems like it should be a pretty easy thing to figure out, well then you haven’t watched much competitive cycling lately.

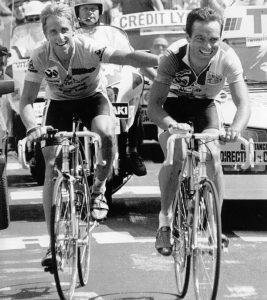

When Greg Lemond won the 1986 Tour de France, it was not clear whether Bernard Hinault was his teammate or his opponent.  In fact, no one’s sure whether Bernard knew.  As far as I can tell, cycling is the only competition where the sport is organized in units of team, but the prize money (and glory) is organized in units of individual.  Imagine if Real Madrid took on Barcelona, but the declared winner was just one player: Ronaldo or Messi, or maybe Neymar or Suarez depending on who happened to score.

As it turns out, Tour de France is not at all like running a 100m dash; it’s more like being in an ant colony.  Within each team of 8 riders, a single queen bee is designated who has the best overall prospect of winning.  The rest of the team become the workers, known as domestiques.  Domestiques shield the queen from the chaos of the peloton (imagine masses of high-flying cyclists swerving down mountains at high speeds, inches from each other and throngs of spectators on either side), they allow the leader to draft to save energy, and they shuttle food and water from the support vehicle.  In the case of a crash, a domestique may even have to give the leader his bike and wait for a new one from the support vehicle.  Domestiques may be allowed to win certain stages.  But ultimately they know their place.

Only, in the case of the 1986 Tour, there were two queen bees on the La Vie Claire team.  At the 1985 Tour,  the new upstart Lemond was the stronger rider than the aging 4-time Tour winner Hinault.  But they were teammates and a deal was struck: Lemond would assist Hinault to his 5th and final victory in ’85, and ’86 would be Lemond’s turn.  The cooperative and stage-based nature of cycling makes such deals quite common.  In fact, one of the strengths of Slaying the Badger is its ability to convey (even to a non-cyclist such as myself) the importance of cooperation, etiquette, and unwritten rules.  However, Hinault continually attacked at the ’86 Tour and seemed to be going for his 6th victory, and then pretended to be teammates on his bad days, to the great consternation of Lemond.

It’s a staggering testament to Lemond’s raw talent that he was able to win the 1986 Tour, against one of the greatest, most intimidating cyclists of all time, and without the customary support (almost all of the riders on team had greater allegiance to Hinault; Lemond surmised that even the coaches and support vehicles favored Hinault).  Has anyone ever won the Tour virtually solo (Lemond had just one ally — fellow American Andy Hampsten)?  Even with EPO, could Lance have won a Tour without George Hincape and his team of highly disciplined minions?

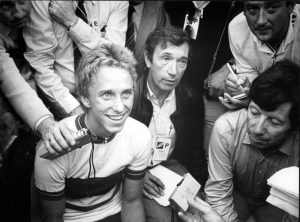

Perhaps equally astonishing is Lemond’s comeback victory at the Tour in 1989, in what is still the closest finish in Tour history (8 seconds).  In 1987 Lemond was pelleted with a shotgun turkey hunting with his brother-in-law.  Lemond lost some 65% of his blood volume, and nearly bled to death.  Surgery could not remove all of the pellets, some of which remain lodged in his liver and the lining of his heart.  He could not defend his ’86 victory, missing two Tours  (’87 and ’88).  In 1989 Lemond returned to the Tour as a non-favorite.  In the final stage, a time trial, Lemond somehow erased 50 seconds over ~15 miles on two-time Tour winner Frenchman Laurent Fignon.  So much for the final stage being perfunctory.

Lemond was able to win one last Tour in 1990, perhaps the last clean Tour before the Era of EPO descended.  There are a lot of things in Lemond’s career that didn’t go his way.  The bullets at the height of his success likely robbed him of a status as one of the greatest riders of all time.  Lemond also could have won even more Tours had his career not run head on into the EPO era that began in the early 1990s.  But the real tragedy is how in retirement Lemond’s reputation and livelihood were smeared by Lance Armstrong, who bullied and ostracized anyone who questioned whether he was clean.  Instead of enjoying a retirement as an exalted Tour hero, even Trek bikes terminated business relations with Lemond because of their discomfort with his outspoken questioning of Lance.

In the post-Lance era, Lemond is making yet another comeback, and finally enjoying the hero status he was denied too long.  One may wonder how Lemond could not be bitter.  About Hinault’s early betrayal, about getting shot in his prime, about EPO cutting his career short, and finally, in retirement, being robbed of his reputation and business — just because he had the integrity to call out Armstrong.  But part of Lemond’s great appeal is that nothing ever seemed to go right for him.  In his ’86 Tour victory, he had three crashes in the final stage.

I’m actually kind of in need of a new hero.  The more I learn about Michael Jordan, and how cruel he was to his teammates, the more his aura dims.  Jordan punched tiny point guard Steve Kerr in the face during practice.  Toni Kukoc is probably still in therapy.  Apparently he would stop passing a guy a ball for the rest of the game if he made a mistake in an earlier play.  At the Wizards, his ceaseless taunts made new 18-year old draft pick Kwame Brown cry every day in practice.  Next to Lance, Jordan may be the second-worst bully in sports.

Against the likes of Lance, Jordan, and Hinault, Lemond’s shy, relaxed nature is especially endearing.  In some ways he reminds me of another childhood hero of mine, Cal Ripkin Jr., whose twinkly blue eyes similarly belied an integrity that harkened back to an older age of sport.  I was in the stands in Camden Yards the day Ripkin tied Lou Gehrig’s record of 2,130 consecutive games, and just a row away from where his home run ball landed.  But Ripkin’s and Lemond’s circumstances couldn’t have been more divergent.  One guy played 2,131 consecutive games.  The other got shot in the chest and missed two Tours.  One guy had his father as team manager and his brother Billy at second base (the Ripkins were a family affair).  The other guy was an orphan on his own team.  At one point, Lemond became so suspicious of sabotage that he started taking other riders’ feed bags in the aid stations.  Lemond also suspected that his own team manager Paul Köchli subversively favored Hinault.  There’s a defining moment in Slaying the Badger when Köchli misleads Lemond about how far back Hinault is in order to get Lemond to slow and wait for him.  At the end of the stage the young Lemond cries like a lost puppy after realizing that he could have won his first Tour had he been allowed to continue his attack.

By the end of Slaying the Badger, you can’t help feeling that Lemond is the Job of professional cycling.  To this day, Lemond can’t exert fully or he risks lead poisoning from the pellets still lodged in his body.  Why does so much misfortune have to befall a talent so innocent?  Is his gentleness his weakness, easily exploited by the alphas?  Do ruthlessness and intimidation always win?  But there is some satisfaction in seeing the tides turn in recent years, when Lance gets stripped of everything, and Lemond, as always, stages an improbable comeback.

Bravo!!! You always discover great stuff. I hereby declare LeMond my new hero as well.

And fuck Lance. I have a special mission to cut down anyone whose Narcissistic Personality Disorder is bleeding the world dry. A worthy purpose, I can assure you having known two really well.