The other day I uncovered a box buried in the closet of my childhood bedroom. Inside was a pair of girls track spikes, grey with a purple Nike swoosh. I turned the shoes over, pressing my fingers against the tiny metal fangs. Twenty years ago, the spikes were sharp enough to draw blood. But time smooths everything, and hopefully by remembering the mistake I made quit running after high school I could stop myself from quitting science as well.

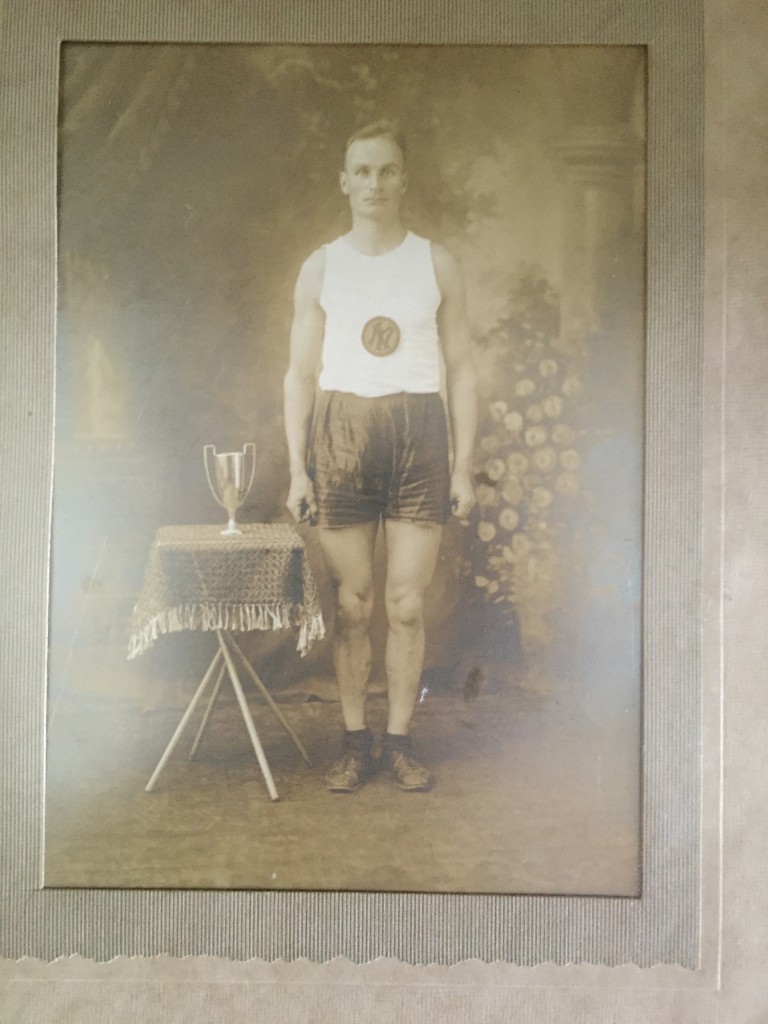

No one was more shocked than I when I won the state cross country title in high school. As a sophomore I became one of the DC area’s promising young runners. But by senior year, it seemed my star had faded. I fought to preserve my 95-pound pixie frame, but as my female body morphed, it became my enemy. I was not alone. Over the last forty years, sixteen girls in grades 9-11 won the national high school cross country championship but never won again. The number of boys in this category: zero. Girls are not less driven. But as testosterone kicks in, boys get stronger and faster. As estrogen increases body fat, girls fall into destructive cycles of dieting and overtraining. I dreamt of following in the footsteps of my Finnish great-grandfather, a professional distance runner, and his brother who ran the Boston Marathon in the 1930s. But the dream faded with each race I lost and ultimately I decided not to run in college.

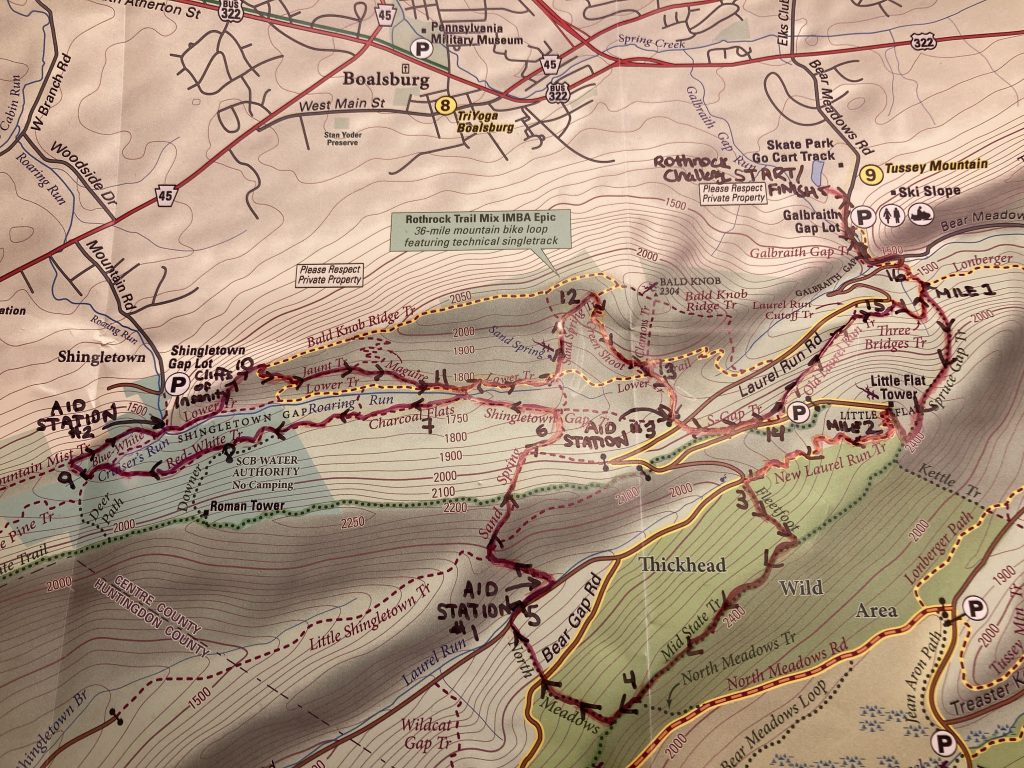

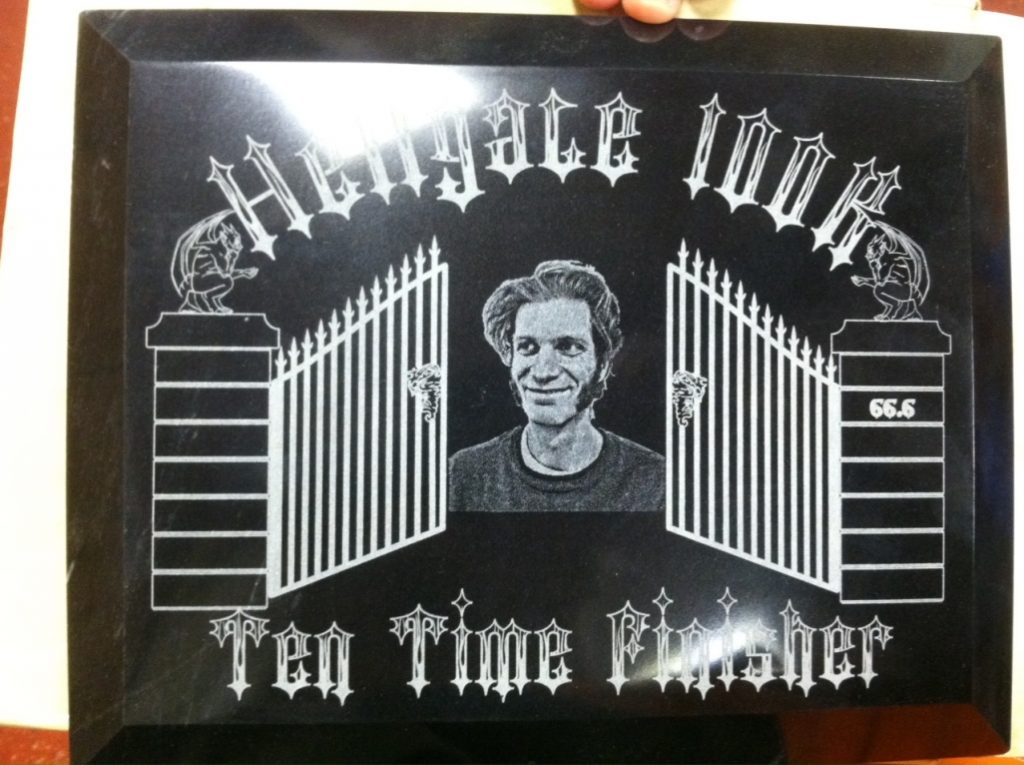

An 18-month break from stopwatches was the salve I needed. One summer I discovered a purer form of solo trail running in the deserts of New Mexico. The brutal sun made it far too hot to run fast. I learned to focus on other things: open skies, fanciful cacti, speeding lizards. Rejuvenated, I joined the college cross country team as a junior and dropped minutes off my 5k to finish All-America. I realized that girls do not need to be pixies, their bodies just need time to adjust. After college I competed in road races, fulfilling my dream to finish top-50 at the Boston Marathon as my grandmother watched from the same corner where she cheered her uncle 70 years earlier. Next I discovered trail races and ultramarathons, the ultimate adventure. In hindsight, adolescence was a temporary phase, a blip. I wish I could have told my teenage self to go easier on myself before I nearly skipped out on a lifetime of adventures.

Twenty years later, I am entering a second life phase that derails many talented women. When I decided to have my first child, I was hellbent on not letting it interfere with my dream job as an infectious disease epidemiologist at the National Institutes of Health using next-generation sequence data to save the world from pandemics. I hauled my eight-month pregnant belly across the Atlantic to give a talk at a virus evolution conference. I finished journal article proofs on my iPhone between labor contractions at the hospital, until my husband locked it away. I knew something like COVID-19 was just a sneeze away.

But the turbulence of early motherhood exceeded my worst-case scenario. Once the baby was out and I appeared physically normal, the reasons behind my struggles became less apparent and harder to talk about. The Federal government granted women no weeks of maternity leave, and balancing nursing and research became a daily struggle for survival. I told a friend I would sooner run a marathon every day indefinitely than endure another month. American women get pushed out of their jobs so frequently after starting families that it has become cliché. Still, I was unprepared when the NIH passed on my promotion last October and announced my postdoc would take over my role leading the genomic program I built a decade earlier. Having a child was double jeopardy for my career because my family became permanently rooted in DC after my son’s birth, nixing the possibility of leaving for an academic post.

Sitting alone in my living room, I wondered how I was expected to simultaneously contend with a job loss, a global pandemic, a childcare crisis, combined with geographical inflexibility that made finding a new job seem hopeless. I began reaching out to colleagues in science policy and journalism to find an alternate career path. My boss’s words kept ringing: You had a good run, but it’s time to pass the torch. I had not been so tempted to abandon a dream since boxing my track shoes.

Several female scientists I know who left research after children later admitted they came to regret the decision, even if it felt forced on them at the time. Nothing replaces the thrill of a new scientific discovery. Recalling how I relinquished my running career just because I hit a totally predictable bump during normal female development helped me avoid repeating the same mistake as a scientist. Instead, I regrouped and found a needle-in-a-haystack position in another branch of the NIH. This fall I’ll head to a new office just as my toddler begins his first day of preschool. Larger kids will surely push him down and snatch his toys, but I’ll share with him a dirty secret that his mom takes the same punches at work. It’s nothing to be ashamed of and whimpering and telling a teacher only brings more trouble. Better to just dust off, redirect, and we’ll find new adventures together.

Realistically, over the decades there has been little change in the competitive systems of distance running and scientific research that spontaneously break young women as they naturally go through rocky transitions, and I have little expectation of future progress. My initial instinct to escape two systems that broke me was based in self-preservation. But I’ve learned, twice now, that quitting is not the right answer and that conditions can improve just as quickly as they deteriorate. In the end, what felt like a career earthquake turned out to be a short detour, just like adolescence as a runner. My experience roaring back as an adult runner gives me renewed confidence that getting flattened can signal the beginnings of a career, not the finish line. Over the next decades my scientific colleagues and I will be working to make sure our children never live through something like COVID-19 again. Or at least die trying.