The Island

In Finland’s boreal forests, just above the Arctic Circle, the sprawling Lake Inari is peppered with thousands of small islands. Graveyard Island served for centuries as a cemetery for the ancient Sami, Lapland’s semi-nomadic reindeer herders. When the pandemic ends I will journey thousands of miles to spread the last of my father’s ashes around the island’s icy blue waters. Lakes were my father’s nirvana, a trait passed down over generations of Finnish ancestors, and maybe there he will find the peace that eluded him in death.

Three years ago the US embassy in Helsinki phoned our family with shocking news. A hotel maid discovered my 74-year old father’s body crumpled in a desk chair in his room. His colleagues had accepted his explanation that his stomach ailed after Korean food when he skipped his conference. An autopsy report determined otherwise. A simple surgery would have removed his ruptured appendix and saved his life.

But my father had a history of not asking for help. He was a broad-shouldered, heavy drinking ox who rebuffed meddlesome doctors. A few years earlier I had to beg him to visit a hospital for a broken ankle flapping around after a lawn mower incident. He snarled like a bear when friends suggested an ointment for the pink fungus spreading like vines from his toes to his groin. I knew better than to try.

Was there a flash of light in his final dying moments when he realized he should have sought care? Or did he drift into death oblivious that he was dying? Alone in his hotel room, poisons seeping within, did he finally learn if God exists, after concluding so in his recently published philosophy book, God? Very Probably?

The week before Christmas my mother, brother, and I hastily packed and flew to iced-over Helsinki to identify his body and arrange for its cremation and shipment back to the US. My mother picked up his ashes at Dulles Airport and we performed the American death ritual as best we could. My father would have been pleased by the three-day fiesta in his honor: academic symposium, memorial, and lobster party, in that order.Â

When it came time to speak at my father’s memorial, I talked mostly about my early childhood, when I legitimately enjoyed growing up in the most eccentric libertarian family in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Family trips across the American West — and later the world — were wild misadventures where overriding my mother’s hesitations was half the fun. My father was larger than life, cruising past Chevy Chase’s mansions in his beat-up Toyota convertible with the roof down, dangling a gin and tonic on ice in his right hand and an unused seatbelt flopping on his left. Dare anyone to stop the shaggy-haired libertarian philosopher-king. My father filled the family dinner table with foreign intellectuals, pumped them with alcohol, and then jovially cut them down and explained why all their thinking was wrong. My friends were awed by my father’s bravado, strength, and sprawling personal library in our basement. There were at least ten thousand books. With a tanned, bearded face framed by shoulder-length dusty blonde hair, women sometimes mistook him for the actor Kris Kristofferson. I thought he was Zeus, all-knowing and all-powerful. Thundering whenever he felt slighted. I was a meek, tiny child who flew under his radar while he was preoccupied by writing and tennis. Only later in high school did I sign up for the high school track team and everything changed.

The Gift

My father was awestruck when his diminutive, squeaky-voiced teenage daughter suddenly could not lose a race, taking the state and county cross country titles as a rookie. My dramatic come-from-behind racing style made for nail-biter finishes and Washington Post headlines. My family was mystified when my 95-pound frame claimed the Maryland state cross country title in a final sloppy sprint across a mud-soaked field to pass the favorite. No one in my family ran except after tennis balls. My father referred to it as the “miracleâ€. Only later did my Finnish grandmother divulge the hidden roots of my success.

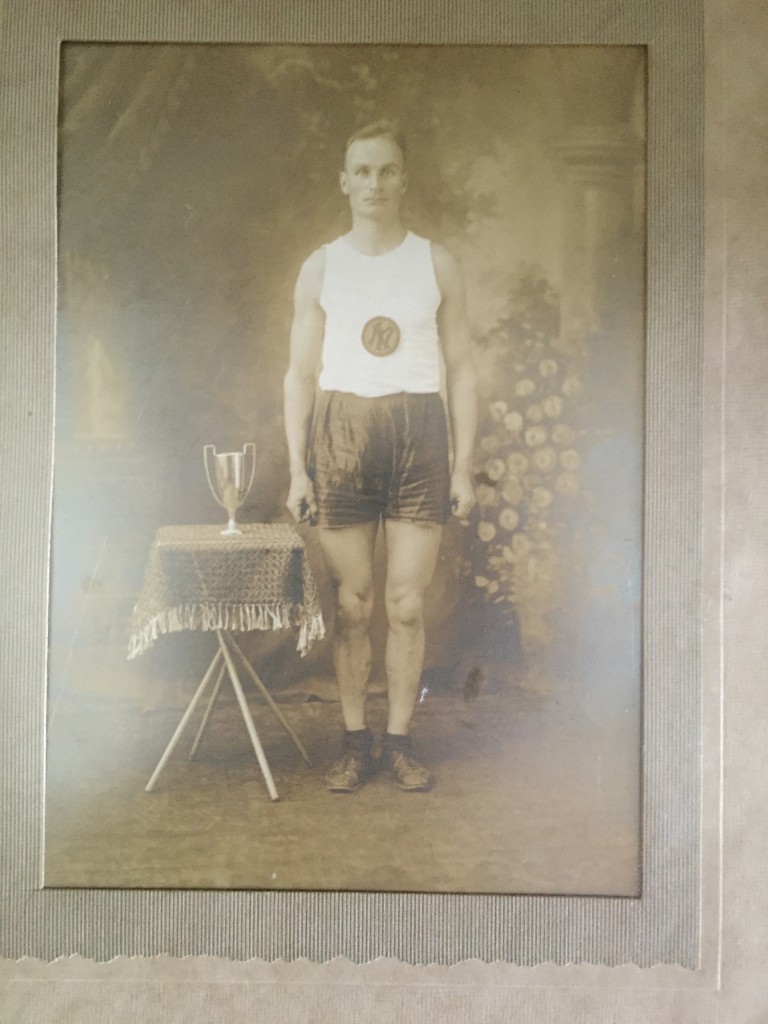

It had been six decades since my grandmother had cheered her father Onni as he raced the mile as a professional distance runner in Boston. Finns ruled distance running in the 1920s and 1930s. Paavo Nurmi, the “Flying Finnâ€, won nine Olympic gold medals. Distance running was a family affair and my grandmother also handed oranges to Onni’s brother Laurie as he ran the 26.2-mile Boston Marathon route from Hopkinton to downtown Boston each year. Back then the marathon was still just a gaggle of a couple hundred Bostonians.Â

Finns claim to have guts, referred to as “sisuâ€, cultivated from youth by plunging their naked bodies into freezing lakes through holes carved in the ice between sauna sessions. The underdog Finns thrashed the Soviet army in the Winter War of 1939-1940, where temperatures plunged below -50F, emboldening Hitler to invade a seemingly weak USSR the following year. Instead the Germans became mired in a bloody eastern front that allowed the Allies to pierce the west. So we can thank the Finns for bringing down the Nazis.

But Onni died suddenly of tuberculosis at age thirty-two. Laurie burned his shoes in disgust and never ran again, blaming his brother’s death on a weakened immune system that had been compromised by Finns’ notoriously harsh training regimens. Onni’s wife Martha raised my grandmother alone, cleaning bathrooms in factories to make ends meet and settling in a fishing town called Gloucester north of Boston. Martha was still living there by the sea when I was born fifty years later. I called her “Mummuâ€, which means “grandmother†in Finnish.

One Christmas my grandmother gave me Laurie’s vintage 1920s diamond engagement ring that he purchased to propose to his soon-to-be wife Elsa. I also inherited something more sublime from Mummu and my grandmother. We all had an uncanny knack for finding four-leaf clovers. I have found thousands in my lifetime, also 5-, 6-, 7-, and 8-leaf clovers. I never find them when I look, only when I sense them when I’m busy doing something else, like running down a trail or riding a bike.

My initial rise as a runner in high school was virtually unsupported. My parents were so unaware they did not even buy me track shoes. I toed the line at my first state championship as the only runner wearing clunky Nike sneakers instead of featherweight spikes. Nor did I get much support from my team, which did not even have the five girls needed to compete as a cross country team. Old Coach Fleming mostly took photographs. Each race I was underprepared, undertrained, and looked like a deer in the headlights. At a state championship where I unexpectedly got my period and had no one to turn to, I shoved piles of toilet paper in my shorts and hoped for the best. But everything changed after I won the state cross country title.

The Self-Appointed Coach

Two weeks after I won the state cross country championship my father, my father signed me up for the Footlocker Northeast Regional Championship in New York City, eager to test me against stiffer competition. The only hitch was that I did not want to run it. I was mentally and physically exhausted after my my rookie cross country season and fighting a stubborn cold. I was looking forward to a healthy break after the state meet. My father, having never run a race himself, had no personal experience with the physical demands of distance racing . Â

On race morning the Bronx barely cracked twenty degrees. My teeth chattered. One mile into the race my throat constricted and a strange wheezing sound emanated from my chest. Alone on the wooded trails of Van Cortland Park, I struggled to breathe. Frightened, I peeled off to the side of the trail until I weathered my first asthma attack. I slowed my breathing enough to finish the race mid-pack. When I got home I was feverish in bed with pneumonia for weeks, my longest absence from school. When I finally returned to the track I needed an albuterol inhaler prescribed by my doctor. The feeling of suffocation became a metaphor for how I began to feel about running — and my father.

My father saw distance running as my ticket to an Ivy League college (preferably Harvard). But one thing stood in his way: the doddering old Coach Fleming. While I was laid out, my father visited my high school athletic director to demand he replace Flemming with a young assistant track coach who had just finished second in the Marine Corps Marathon. Fleming’s light touch worked well for me, as I was already practicing soccer with my travel team 3-4 days a week. Chronically underweight and fighting off colds, I was a risk for burnout.

One night the ABC evening news aired a TV segment “Teens in Trouble†where I delivered a deadpan account of what exhausted teens face on a daily basis, logging long hours of school, sports, and homework under intense pressure. I spent the next day in the offices of alarmed school administrators. I fell on my grenade, promising I wasn’t suicidal, cutting myself, anorexic, or being abused. I was mortified when teachers took me aside after class to ask in hushed voices if I was okay. In retrospect this was my opportunity to get help. But no one was a trained therapist. No one knew what questions to ask.Â

The Mistake

Warmer spring weather improved my asthma and the next spring I prepared to race the mile at the track and field state championships. I only needed to finish top-4 at regionals to qualify. May is hot and humid in DC and billows of steam rose from the black track after a morning rain. A few steps into the regional race I felt my silver chain bounce against my collar bone. I rarely wore jewelry but had gone to sleep wearing a Navajo necklace with five colored stones. I was tired after staying out late with friends the night before. Jewelry was not allowed, so I immediately popped into the infield and unclasped the chain before dashing back onto the track. A line of girls in bright singlets already bobbed away around the first turn. I chased after them, hopelessly behind. What an awful way to end a season. I fought back tears. I was still dead last at the halfway point.

But passing the last-place straggler energized me. I clawed my way back into the race. I wheeled around the final lap, weaving and bobbing through a thick pack of racers. I could hear my teammates Alpha and Maduba screaming and jumping on the bleachers. I dashed towards the finish line and barely edged out the fourth place runner, earning the last spot in the state finals. I threw up my hands as if I’d won.

A race official with a clipboard sidled next to me. His large belly protruded over his belt and a cap shaded his eyes. He told me I was disqualified. I was still panting too heavily to respond. My coach leapt into the infield to clarify the decision. I had worn the necklace for only a couple steps. The only performance affected was mine. But the official stood firm. My glare could have burned a hole through him. Like my father, he had clearly never run a race in his life.

I was prepared for my father to leap into the fray, unleashing one of the fits of rage he displayed on the tennis court. But he stayed put. When I approach my parents at the fence I realized my father’s anger was directed only towards me. He slipped into economist-speak, offering unrealistic solutions engineered for a hypothetical world. You know, if you had really been thinking you would have run back to the start line to take off the necklace. I furrowed my brow, not catching his drift. There’s a rule against wearing jewelry, but I bet there’s no rule against starting a race late. I looked away in disbelief. Actually, your mistake was taking the necklace off in the first place. Probably no one would have even noticed if you hadn’t drawn attention to it. The Monday morning quarterbacking kept coming, the whole drive home. Do you have a mental checklist that you go through in your head before every race? It was a solemn dinner at home.

The Downturn

Mistakes are teachable moments and I learned an important lesson that day: my father only showed affection toward me when I won. There was not even a flicker of warmth for gutting it out when the winds were against me. He trotted me out at cocktail parties to brag about my victories to his friends, beaming with fatherly pride. But it was exhausting to have to win races in exchange for parental affection. Behind the scenes he took little interest in my well-being. As a teenager I once called my father from a party asking him for a ride home because I had been drinking beer. He was busy watching tennis and assured me I was fine to take the wheel as long as I was careful.

My father and I had different views on racing. He wanted me to fix the unevenness of my quarter-mile splits, convinced I was being overly conservative during my third lap and intentionally shoring up reserves for the final fourth lap. He did not realize that even professionals run wildly uneven splits. He pressed me to lead every race aggressively from the front and hang on to the lead until I collapsed, even if happened mid-race. “Think of it as an experiment,†he explained. “To test your limits.†I had seen girls carted off in ambulances and was uninterested in being his guinea pig.

During my sophomore year, I got my period and my teenage body started morphing into adulthood, exacerbating the disconnect between what my body could do and what my father thought it could do. My self-confidence nosedived as I began to blame my fleshier body for my slower times. My father assumed my times were getting slower because I was choking and having psychological problems that many tennis players face under pressure. My father hired a sports psychologist to fix me.

My first encounter with a trained therapist was eye-opening. In retrospect, it would have been helpful to have more sessions with him. He was gentle and kind. He assured me I was not neurotic, lazy, or timid. But he did not manage to “fix” me, so I only saw him once. Over my junior and senior years, I became emotionally numbed, counting down the days until I left for college.

Fly Little Bird

When it was time for me to select a university, my father dragged me to every elite university in the country, whether I was interested in going there or not. I interviewed with the track coaches, even as I was counting down the days until I never had to run again. We trekked across each campus to find the main library so we could count how many political philosophy books he authored were in the catalogue. There was no pretense that the university excursions were not really about him.Â

I decided I wanted to go to Amherst College, a small liberal arts college in a cozy New England town, nestled in the pine forests of the Pioneer Valley, surrounded by woodland and farmland. I could imagine being happy in the home of Emily Dickinson and Robert Frost, running on my own through the forests.Â

My father made me apply early to Harvard instead. He assured me I didn’t have to go if I got in. When Harvard mailed my early decision letter in December 1998, my father did not wait for me to get home from school to open it. He snatched the letter and ripped it open himself. The single act summed up our relationship perfectly.

I did not end up going to Harvard, or Amherst, or any school on the east coast. I fled to the west coast to Stanford University. The school had the distinct advantages of (a) satisfying my father as elite enough, (b) being thousands of miles away, and (c) never recruiting me to run. I couldn’t wait to exchange track spikes for flip-flops.

Second Act

Kicking back and soaking up rays on the laid-back west coast was supposed to make me feel relaxed. A Stanford degree was supposed to make me feel successful and secure. Instead I felt listless. I had fled west like a frightened deer. It was time for me to be the hunter.

Everyone assumed I was having a nervous breakdown when I left Stanford after my first year. My stunned California friends had never heard of Amherst and thought it was a community college, confusing Maryland and Massachusetts (too many little east coast states). I didn’t bother explaining myself to anyone. I twirled Laurie’s ring around my fourth finger and for the first time did exactly what I wanted. The next year, I became the fastest distance runner on the Amherst track and cross country teams, finishing All-America at Nationals. I liked dashing through the woods.

Night at the Colobus

The next summer my father celebrated his 60th birthday by climbing Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania with me and my brother. A few days before our climb, my brother and I were playing the “flaming sambuca†game with friends. You dip a finger in sambuca to pass a flame around the circle. Whoever loses the flame must drown their shot glass. Afterwards we picked up my father and headed for the Colobus nightclub on the outskirts of Arusha. I did what any carefree 21-year old girl does at clubs: dance, let others buy drinks, try not to get molested. I was oblivious to the fact that my father spent most of the night brooding alone at the bar, feeling ignored and slighted. No one wanted to converse with him about politics. So he drank and stewed. By 3am he was slurring his words and could barely walk to the car. In the parking lot he erupted. I had treated him like an old man. I had not welcomed him into the circle of young people I was dancing with. I had made him feel “like shitâ€. I slunk into the back seat of the car and let my father take a turn screaming at my brother while we drove home. I never went from drunk to stone cold sober so quickly. I had witnessed his explosive eruptions at many friends and family members, but this was the first time it was directed at me.

Years passed before I understood the source of my father’s explosion and how deeply he dreaded turning 60. The Kili climb was designed to prove his virility and youthfulness. But he was anxious. What if he failed? Such doubts had plagued him for some time. Unbeknownst to me, he had treated severe performance anxiety with alcohol and antidepressants since his twenties. As a graduate student at Princeton he was treated by psychiatrists for panic attacks. When he began teaching at city college in New York City, he drank scotch before lectures. He claimed alcohol calmed him better than any therapist. Until it didn’t.

Adulting

The following summer I landed a summer internship in Moscow at the US State Department. My father insisted on tagging along and renting an apartment in Moscow for the entire summer. I objected. Moscow is a rough city. He couldn’t even read Cyrillic. I was overruled. Fortunately, the US embassy’s many layers of security made it impossible for him to visit me unexpectedly. But I had recurring nightmares of my father drowning me in a friend’s pond scattered with lily pads in upstate New York. The sunlight at the water’s surface faded to black as I was pushed to the pond’s floor, with icy fingers around my throat, entangled in the long, thin roots of the lilies.

White Knight

I spent my early twenties globetrotting across Australia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe, carving my own path. But by age 27 I had settled in DC for a postdoctoral fellowship. Back in the family orbit I began to regress. Until I met Aaron.

Aaron and I dated for a few months before he announced there was a problem. He objected to my intoxicated father driving me home to DC after Monday night dinners at my parents’ house in Chevy Chase. I was dumbfounded. Drinking and driving was normal. In my earliest childhood memories I sit shotgun while my father drives on the Beltway with a gin and tonic in his hand. Even today, the scent of gin reminds me of breezy summer car rides. The Monday car ride was supposed to be my quality one-on-one time with my father. I relayed Aaron’s objection to my mother, but neither of us acted.

But Aaron stood firm and eventually my mother took the car keys. She could not risk driving away the first nice Jewish boy willing to put up with her moody daughter. Eventually I decided that Aaron was not being stubborn or difficult. I was just witnessing something novel: protection from someone who cared about me. A few years later my father passed out driving home from a DC party, drifted across the double lane, and crashed into a fire hydrant on the west side of Oregon Avenue. He was still passed out when cops arrived. Aaron was vindicated.

Aaron continued to contest my belief system. Our first summer dating we both ran the Highland Sky 40 mile ultramarathon in West Virginia. He won handily but I had stomach problems and dropped out after 32 miles. The next morning I forlornly flew to a work conference in California convinced I would never see Aaron again. I strolled along the beaches of Santa Barbara wistfully watching the pelicans dive, accepting that I had blown it. I wallowed in guilt and shame. I was stunned when I returned to DC to find Aaron’s demeanor towards me unchanged. I had not fallen off some pedestal. He was even more flabbergasted that I believed I was unworthy of him just for flubbing one race.

Over time as Aaron became acquainted with my father he began to grasp the roots of my curious outlooks. Whenever I started to disparage myself, Aaron would tell me That’s your father speaking. Disparagement came so reflexively it was nearly automatic. We referred to it as my brain chip. I set radically different standards for myself and my friends, whom I never judged based on their performances. Aaron helped me set boundaries with my father for the first time. He became a go-between. My father took direction from men more easily than women. Plus, my father respected Aaron’s knack for fixing all his computer and A/V problems. Moreover, Aaron was willing to engage in political debates the rest of the family had tired of. My father always needed “fresh bloodâ€.Â

At times I tried to repair relations with my father and broach some of the difficulties I faced as a teenager. How it felt to have my legs cut out from under me. How I felt he invaded my space. But he would brush me off, never wanting to revisit “water under the bridgeâ€, the same way he never addressed his own problems with his father, which haunted him to his last breath. When I leave this earth I don’t want to be carrying that kind of baggage. Some people will think it excessive to travel thousands of miles to dump my father’s ashes in a remote lake at the ends of the earth, but they have no inkling of the distance I’ve already traveled.

Thank you for being open and authentic. What a story.