I lay in bed with my eyes closed, listening for indications that Finn was up and mobilizing. Last night I had questioned the necessity of the early rise – it was Saturday after all – but Finn insisted that early morning was the best time to run. Finn had a 5 kilometer loop that he professed to be the most beautiful in Sydney.

We were laced up by 8, but the Australian sun was already strong, and Finn insisted I carry a water bottle. I assured him that I could trot 5k without water. But the loop had steep rocky ascents, and apparently Finn’s cousin had succumbed to heat exhaustion once before. On good days, Finn said he could do the loop in around 42 minutes, but he hadn’t been running much and he expected to be closer to 44 today. I promised him I wasn’t wearing a watch.

I slathered on sunblock, and we trotted off through the seminary woods. Noisy rainbow lorikeets shot between gum trees, and enormous sulfur-crested cockatoos bobbed their heads in the branches above. Water dragons sunned themselves on the rocks.

Giant rabbits – the bane of the Australian ecosystem – bounded through the fields. I told Finn how Eddie, my former PhD advisor whom I had been visiting the prior week at the University of Sydney, has been doing some ‘bunny experiments’ to study the host-pathogen dynamics of the myxoma virus that the Australians had introduced several times to try to control the exponential growth of the non-native rabbit population that was destroying Australia’s ecosystem. Although the virus initially caused severe hemorrhagic disease in the rabbits, the rabbits quickly evolved resistance and populations resurged. It’s a rare example of biocontrol, and a beautiful system for studying the host-pathogen arms race. The intentional introduction of multiple non-native species from Europe and Asia has wrecked havoc on Australia’s unique ecology. Rabbits, foxes, and boars were introduced for game; camels were introduced to build the railroads (horses did not fare well in Australia’s scorching deserts).

The ecological history of Australia is a string of human follies, the most infamous example of which is the introduction of the Cane toad. The Cane toad was introduced from South America as a predator of the Cane beetle that was decimating Australia’s sugarcane production. Instead, the Cane toad ate everything but the Cane beetle. Furthermore, the Cane toad is highly toxic, and kills any carnivore that consumes it. The Cane toad presents the greatest threat to Australia’s wondrously unique marsupial population, and Aussies are encouraged to kill any Cane toad they come across by whatever means possible – smashing it with a bat, driving over it with a car – but the Cane toad continues to grow in size and spread in range.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4mvV8OT-mmE

I had visited the Pursells in Manly previously, and the trails were all vaguely familiar. It was a marvelous little loop, climbing up a natural rock staircase cutting through the thick brush. We took a break at the top to enjoy the expansive view over Sydney harbor. Finn pointed out ‘spider alley’ where the trail becomes thick with cobwebs hosting giant spiders in the evenings. Finn had admitted to coming across a giant huntsman spider in the house the previous day that had kept Sarah and me on high arachnid alert all night.

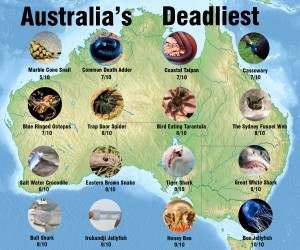

Australia is notorious for its oceanic hazards: great-white sharks have been observed right in Sydney harbor, riptides are a major cause of death, and stinging jellyfish require beach-goers to wear protective suits that look like giant condoms during jellyfish season. But no trip to Manly would be complete without some ocean adventure, and Sarah joined us for post-run snorkeling. I’m not sure I’ve ever swum in such cold water. But Finn has infectious enthusiasm, and in no short time I was too distracted by the schools of fish and soccer ball-sized purple sea urchins. We swam point-to-point to Manly beach, one of Sydney’s most popular beaches, which was teeming with weekend visitors.

After some recovery hot showers and snacks, Sarah, Finn, and I hit the road for the Blue Mountains, where Finn lives and teaches piano at a local conservatory. Finn was already pretty tuckered by the morning activities of running and swimming, and was inclined to do a short hike in his neighborhood that afternoon. But Sarah and I had limited time to enjoy the Blue Mountains, and pleaded with him to take us on the more vigorous excursion option that was a bit farther afield.

When someone tells you to wear long pants in Australia, you should probably find yourself some body armor. Australia has the most poisonous snakes in the world. Finn also told us that it was currently peak snake season in the Blue Mountains, and the likelihood of seeing a snake was quite high.  He regaled us with stories of venomous snakes in his backyard, venomous snakes that he had almost stepped on. ‘Just be careful where you put your hands and your feet,’ Finn suggested. Right.

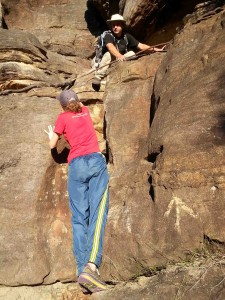

‘So this part is a bit tricky,’ Finn warned. We had deviated from the main path and had walked to the edge of a tall cliff. We couldn’t see the bottom.

Before Sarah or I had a chance to ask whether this was actually a good idea, Finn was already shimmying down. ‘It’s just like non-technical rock climbing,’ he assured us.

Getting down those rocks required ample use of the butt-slide and coordinated hand-offs of our walking sticks so we could use both hands. Finn assured us that climbing back up would be easier than getting down.

Once we got the hang of it, it was actually a great thrill to navigate our way deep into the gully. Sarah and I kept marveling, ‘There’s really no basis for it, but Finn seems to have a lot of confidence in us.’ Finn had been my neighbor growing up, but I hadn’t seen him in over a decade. And this was his first time meeting Sarah. We could think of a lot of our friends – men and women alike – who would not have been game at all for this harrowing descent. We wondered if Finn did this with all his visitors, a right of passage kind of thing. Or maybe he didn’t get many visitors.

‘This was NOT in the brochure!’ Sarah and I kept joking, in homage to Kurt, a California dude from years ago who had showed up to the Mount Kilimanjaro climb decked out head-to-toe in every piece of gear in the REI catalogue and who had shouted that very quote in objection to a brief rock scramble that apparently had not been sufficiently described in the tour’s info materials.

But the challenge was worth it: at the base of the descent was the most tranquil setting of interconnected freshwater pools and waterfalls. Looking up at the wall of mountains surrounding us, there wasn’t another soul in sight.

We stripped down to our bathing suits. ‘So, Finn, are there snakes in the water?’

‘No, the snakes won’t be in the water if we’re in. They don’t like people.’

I furrowed my brow. But the water was so fresh and inviting, we plunged in anyway. You could scramble across the rocks between pools and we traveled through the network of pools for about a kilometer. A wedge-tailed eagle darted overhead. Wood ducks foraged with their bills. We sat under the waterfall and let the cool torrents pour over our head and face.

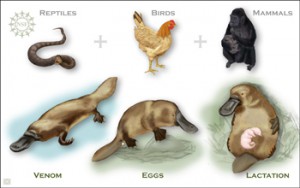

Just as we were deciding whether to continue on through another pool, all three of us saw a dark creature moving along the surface of the water. I had snakes imprinted in my mind and first thought it was a water snake. Sarah saw its little eyes peering over the water and thought it was an alligator. But when it dove under we saw its furry little sausage body.

‘A platypus!’ Finn exclaimed. We waited silently for another ten minutes to see if it would resurface. But platypuses are one of the most secretive mammals on the planet, and that one little glimpse was all we got.

In all of Finn’s years of hiking and camping in the Blue Mountains, he had never before seen the elusive platypus. In fact, they are so rare that the websites don’t even mention that they live in the Blue Mountains (although their range stretches all along Australia’s east coast). The platypus is such a bizarre little critter, with its duck-like bill and webbed feet and little venomous spurs (I swear everything in Australia is venomous). The platypus is an ancient relic, a mammalian monotreme that lays eggs.

When I had studied abroad at the University of Melbourne during my junior year of college, I had desperately, of all the animals, wanted to see a platypus. I had scoured Tasmania and Queensland, areas where the animal is more abundant, with the hope of a sighting, but to no avail.  And there, in the Blue Mountains, in the least likely of places, I fished my wish. We climbed back up the cliffs, bubbling with excitement, and feeling that we had come across a magical place. It was as if Sarah and I had followed Finn down a rabbit hole into a strange kingdom where mammals have bills and lay eggs.

I started concocting stratagems to get Aaron to come out here, to experience this magical little place. Finn hit the nail on the head: apparently there is a famous 100km race in the Blue Mountains that is held every May (late fall Down Under).

Living out in the Blue Mountains is isolating. Finn’s main human contact seems to be with a neighbor whom Finn believes has been sabotaging and poisoning his trees and garden (at the time of our visit Finn had just acquired some surveillance cameras and had set up trip wires around the sides of his house). Given Finn’s fondness for the outdoors and for running, I tried to convince him to join the local trail running group. Despite many lines of argument I could not overcome Finn’s conviction that 50km was an absolutely absurd distance. Just as I had finally given up and started walking into another room I turned my chin over my shoulder: ‘You know, Finn, there could be cute trail runners.’

His eyes widened and he scratched his chin. ‘Hmm, you have a good point there.’