Abstract

Sean, Miles, and Daniel designed a killer five-day adventure itinerary for me and Aaron in Frisco, Colorado. For anyone headed yonder, here are some tips to maximize your summer adventure within the constraints of altitude.

Introduction

In the fall of 2016, Sean stunned the VHTRC by deciding suddenly to sell his home in Leesburg and move permanently to Frisco, CO. The move drove a dramatic improvement in the quality of life of Mr Andrish, including the arrival of his service dog Miles, a yellow lab who is the first known creature to rival Sean in pure love of mountains and trails. Sean’s airy condo has views of mountains on all sides, and a paradise of trails for running, skiing, and snowshoeing. World class downhill skiing is just a free shuttle ride away at Copper Mountain. Mountain air has also been good for healing Sean’s post-surgery knee, which has been letting him trail race again.

Aaron and I also made last-ditch efforts to link up with other recent Colorado transplants, Daniel and Phil. Daniel and his wife Jenny recently introduced baby Lilia to the world, who we’ve only gotten to know via Facebook to date. I was particularly concerned that their wonderful cat Buster might need extra attention. But I’m afraid I don’t have the Wechsler gene for planning, and we only managed to link up briefly with Daniel, and will have to plan better next time (including getting a rental car) if we want to make it to Golden.

Results

Tip #1: There will be blood. You can’t control everything in a good adventure. You can try to do everything right: slather sunblock head to toe, bring enough water, stash extra clothes in case the weather changes suddenly, which it is bound to do in the West. But there will be blood. In my case, the gore looked more gruesome than it really was: just a gusher of a nose bleed.

I just stuffed my right nostril with tissues and moseyed along. Sean, on the other hand, got a real doozie of a hand gash after taking a wicked fall that slammed his shoulder into a tree. Sean is accustomed to taking a slide, but this one was so painful he went into a kind of shock and had to sit down for a while. The Andrish Family Way is to stick some leaves in there and move on. But Sean accepted my demand that we take him to the hospital and get him stitched up. Sean’s ER doc told him he could still run, but I doubt he’d guess we’d do another epic run the next day, shuttling to Copper so we could make our way back to Frisco via Uneva Pass. Since when did a little blood keep an Andrish down?

Tip #2: the Kite Lake Trail is an efficient way to bag 14ers. The plan for our five days in Frisco could be summed up as: bring running clothes, show up. So when Daniel announced that he could arrive at 7am on Friday and drive us to the Kite Lake Loop for our first big adventure, we were totally game. The Kite Lake trail takes you over four mountains over 14,000 feet (Mt. Democrat, Mt. Cameron, Mt. Lincoln, and Mt. Bross) over a mere eight miles. You’d be hard-pressed to find a more efficient way to bag a handful of 14ers.

Tip #3: Take an Easy Day. On your first adventure, you’re going to have an altitude-be-damned attitude and push through the dizziness and fatigue because you’re just so stoked to be out there. Your lungs will burn, your head will spin, but you’ll soldier on. But take a tip from the ole marmot and back off the next day. Summit County’s event calendar is chock full o’ fun stuff all all summer, and a quick glance at a local newspaper will yield a host of activities that won’t burn your lungs.

Since the Kite Lake trail had knocked the snot out of the two sea level-dwellers, we took the free shuttle to Breckenridge and began Day 2’s adventure with the Summit Foundation’s Great Rubber Duck Race. Over 10,000 rubber duckies were released into the river, and the winner got $3,000.  Someone finally came up with a better way to raffle. We topped off the festivities with awesome Higgles ice cream, and a free gondola ride up Peak 7 [Tip #4: Free gondola rides are offered at Breckenridge all summer long.] so we could so we could cruise eight miles downhill on the beautiful Peaks trail all the way to Frisco [Tip #5: Point-to-point adventures are made dead easy by the Summit Stage, which runs a free shuttle every half hour between points of interest, including Frisco, Copper, Breckenridge, and Keystone].

Someone finally came up with a better way to raffle. We topped off the festivities with awesome Higgles ice cream, and a free gondola ride up Peak 7 [Tip #4: Free gondola rides are offered at Breckenridge all summer long.] so we could so we could cruise eight miles downhill on the beautiful Peaks trail all the way to Frisco [Tip #5: Point-to-point adventures are made dead easy by the Summit Stage, which runs a free shuttle every half hour between points of interest, including Frisco, Copper, Breckenridge, and Keystone].

Tip #6: Skip the race. Our visit coincided with the Breckenridge Crest Mountain Marathon, Half Marathon & 10k, a temptation most VHTRCers wouldn’t have been able to resist. I get it: races are a good excuse to travel and see beautiful parts of the world. But why exactly do you need an excuse? Can’t you just go out to visit Sean and Miles and run in the mountains? We covered some of the same trails as the marathon course, but we got to all run together, giggling and farting, and stopping for all the views and all the critters. And there were a lot of critters.

Critter highlights: Mamma moose with calf, yellow-bellied marmot, pika, steller’s jay, hummingbird (females are tough to ID but possibly black-chinned), hummingbird clearwinged moth (that was originally mistaken for a hummingbird), clark’s nutcracker, snake (unidentified), sharp-shinned hawk, red-tailed hawk, black-billed magpie

Tip #7: Wait a couple days for your big adventure. We arrived in Colorado on a Wednesday evening, and it wasn’t until Sunday that we felt like we’d adjusted to the altitude enough to have the big adventure of the trip. The run around Buffalo Mountain was the highlight for me. Not as otherworldly as Kite Lake, but just pure pleasure. Waterfalls, sweeping vistas, and, maybe most critically, peaks where you weren’t freezing your ass off and could just bask in the sun for a while and watch the marmots scurry through the rocks. Where Miles had plenty of water to frolic in, and where the scenery was always changing, from pine-floored forests to meadows peppered with wildflowers. It reminded me in many places of Fat Dog. Sure, Sean and I ended up covered in blood (see Tip #1). But this is the day I’ll recall when I need to go to my ‘happy place’.

Tip #8: Encore. Always encore. We might have reeled it in after our the Buffalo Mountain bloodbath. The irony of Sean’s fall is that it was actually in one of the least technical stretches, as we reached the popular, groomed Lily Pad Lake trails down at the bottom of the mountain. Sean had no trouble with the boulder fields, but meandering tourists are a whole ‘nother thing.

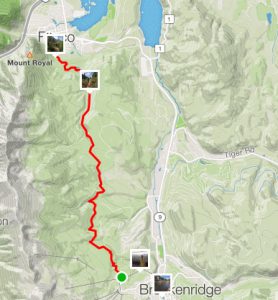

But I’m so glad we rallied for a final point-to-point adventure, taking the Summit Stage out in the other direction to Copper Mountain so we could run back to Frisco on yet another route. We went slooow, demonstrating to Sean just how long a human could spend watching marmots. But we managed not to incur any more blood, and found some unexpectedly beautiful country on some less-traveled trails.

Tip #9: Everything is more fun with dogs. Creatures tend to fall into one of two categories: spirited or obedient. Miles is rare for being both. One moment he’s thrashing in a lake like a puppy, then crashing through the forest understory chasing imaginary prey. Miles is a force of nature, a true athlete, and at the young age of two we’re only beginning to see how far he can go in the mountains (I suspect very far). But Miles also takes his service responsibilities seriously, obeying Sean’s commands like they’re gospel. One thing Miles is not is a guard dog. When another dog snarled and snapped at Miles while we were in line at the coffee shop, the poor sweet thing bounded into my lap for protection.

Discussion

Mission: Frisco was another glowing example of the success of the concept of Noncation. With the three-day weekend and the relatively short stay, there wasn’t quite as much work accomplished as when we do longer 10-day trips. But there is something wonderful about just crashing at a friend’s and not having any of the standard stresses of vacation: (a) the sinking feeling that you’re going to have hundreds of emails when you get home; and (b) the pressure that you need to do everything, because this is your one chance. We covered a lot of territory, but we left a long list of things we didn’t get to do in Frisco. We never climbed Mt Royal. We didn’t make it to Golden to see Jenny, Lilia, and Buster. We didn’t join Phil and Kim in Leadville. We didn’t make it out to Aaron’s childhood neighbor’s ranch in Eagle (ponies!). But, we can leave with the comfortable knowledge that we’ll be back. Sure, there’s a place for real vacation, and I’d like to go somewhere exotic like Brazil or Kyrgystan (someone is still owned a honeymoon….). But in the mean time there’s something absolutely wonderful about vacations that involve zero planning.

The trip was also a proof-of-concept that Martha and Sean can spend five whole days together and not want to rip each other’s face off. Back in the day in Woodley Park, there were loads of good times, but there were also times when Sean’s stubbornness brought me to my knees. I guess Sean left all the old ticks in Virginia, because in five days in Frisco I couldn’t even manage an eye roll.

Materials and Methods

Running gear. You know I’m not a big gear person, but I have to give a shout-out to my new Ultimate Direction Groove Stereo waist belt. I noticed it on Adam W. when he did Highland Sky back in June and hit him up for the details. It impresses me in terms of comfort, including not making me as hot as a vest, and storage, including a nice front pack. I’ll add that Sean and I are also big fans of the Saucony Peregrine trail shoes.

Food and beverage. I would also add that if you’re heading to Frisco, there is great food to be found at Tavern West (a bit more upscale) and a new Mexican place near the Whole Foods called Rio Grande (casual). Great ice cream can be found at Breckenridge’s Higgles. For coffee, head to Rocky Mountain Coffee Roasters on Main Street. And your best local dive bar is definitely Moose Jaw, where we dragged Sean to play billiards even with his hand freshly stitched. Why most women can’t properly wield a pool cue remained an unresolved question, even with hours on the trails to come up with plausible hypotheses. Sean provided a useful insight that he learned to shoot pool in the basement of his college fraternity, while his sister’s sorority had no table. But this just seems to beg the question of why women don’t take up such an elegant sport that doesn’t require any male muscle strength. The marmot would like to know!

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Sean Andrish, for so kindly sharing his space with a bear and a marmot who is not always so tidy. A big thanks also to Miles, who was like the rainbow jimmies on an ice cream scoop and just made every grand adventure sparkle that much brighter. A thanks also goes out to the cute PA at Summit County Hospital who made Sean’s visit to get stitches a lot more pleasant. Daniel deserves a big shout-out for enabling our adventure to Kite Lake. We can get around pretty far in the Summit Stage (which also deserve a big acknowledgment here for shuttling our asses around for free between restaurants, trail heads, and medical centers all week), but we wouldn’t have been able to do that awesome hike without Daniel’s truck. We also appreciated Daniel’s colorful commentary, which could be considered a different flavor of jimmies. Finally, we’d like to acknowledge a nameless group of hikers who very kindly gave us an entire bottle of water when Sean was sitting on a rock in a state of post-trauma shock after splitting open his hand.